2.1. A Beginners Guide to Esperanto

You are going to read an article about Esperanto.

To the doctor who invented it, it was the key to world peace; yet to Stalin it was dangerous, to Hitler a sign of creeping Jewish domination, and the American army dubbed it 'the aggressor language'.

Bialystok, in the 1860s, was no place to grow up. A city in the north-east of what is now Poland, it was at the time under Russian rule. Violence between ethnic Poles, Russians, Germans and Jews was commonplace, and every week brought fresh news of barbarism and cruelty between these isolated and mutually intolerant communities.

It was here, where lack of understanding translated readily into racial hatred, and racial hatred begat violence, that, in 1859, Ludovic Zamenhof was born to a language teacher and her linguist husband. By his mid-teens, young Ludovic had seen enough of man's inhumanity to man to convince him of the need for a common language that would facilitate understanding between peoples.

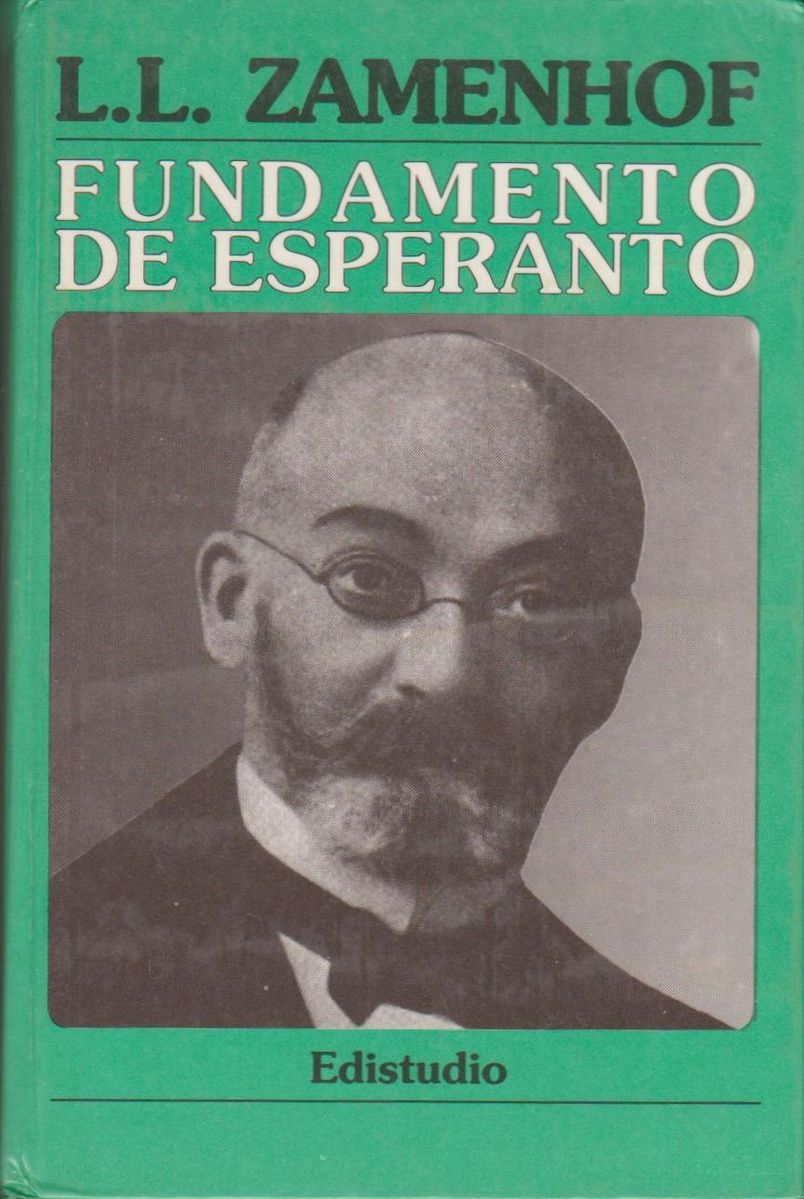

|

| Image by Simtropolitan in Wikimedia.Public Domain |

Having been brought up to speak Polish, German, Russian, Yiddish and Hebrew, and having a good knowledge of English and French, Zamenhof knew that no existing language would fit the bill. For one thing, the fact that they were associated with a particular country, race or culture meant that they lacked the neutrality any international language would need in order to be accepted. And, for another, the fact that they were weighed down by copious rules, yet at the same time were riddled with illogicalities and exceptions, meant that they lacked another essential characteristic of a universal second language: ease of learning by ordinary people. This difficulty factor also ruled out Latin and classical Greek - all of which left Zamenhof with only one option: to devise his own language.

But inventing languages doesn't pay the bills, so Zamenhof studied medicine and became an oculist. By day he fixed eyes and in the evening he wrestled with problems that would make a poet weep. How rigid should he be in his pursuit of simplicity? Was it possible for Shakespeare in translation to sound like Shakespeare? At what point should he stop listening to his head and begin hearing with his heart?

He wasn't alone in treading this difficult path. Pascal, Descartes and Leibniz all toyed with constructed languages, and Johann Schleyer, a German cleric, was even then working on his own creation, Volapük. But whereas Schleyer's language was considered alien and ugly when it appeared in 1880, Zamenhof was to craft a language that many regarded as a thing of beauty. Moreover, while Volapük was almost as hard to learn as Latin, Zamenhof's language was to have only 16 basic rules and not a single exception. It is probably the only language to have no irregular verbs (French has 2,238, Spanish and German about 700 each) and, with just six verb endings to master, it is reckoned most novices can begin speaking it after an hour.

Rather than create a vast lexicon of words, then expect people to learn them all, Zamenhof decided on a system of root words and affixes that alter their meanings ("mal-" converts a word into its opposite, for example). And because word endings denote parts of speech (nouns end in "-o", adjectives in "-a", etc), word order is immaterial. Although modern Esperanto now has around 9,000 root words, most meanings can be expressed by drawing from a pool of about 500 and simply combining them - a creative process that is regarded by Esperantists as acceptable and even commendable.

Three-quarters of the root words are borrowed from the Romance languages, the remainder from Germanic and Slavic tongues, and Greek. This means that around half the world's population is already familiar with much of the vocabulary. For an English speaker, Esperanto is reckoned to be five times as easy to learn as Spanish or French, 10 times as easy as Russian and 20 times as easy as Arabic or Chinese.

While critics seize on the obvious downside of this Eurocentricity - namely that it puts speakers of other languages at a disadvantage - Esperantists argue that the regularity and simplicity of Zamenhof's scheme quickly outweigh any lack of familiarity with root words, and point to the popularity of Esperanto in Hungary, Estonia, Finland, Japan, China and Vietnam as proof of Zamenhof's pudding. Apart from its logical construction, Esperanto has another appealing characteristic: it is phonetic and orthographic, meaning that each letter represents only one sound, and each sound is represented by only one letter.

In 1887, at the age of 28, Zamenhof was ready to go public. His first brochure on the language, just 40 pages long but setting out the entire structure, was published under the pseudonym "Doktoro Esperanto" - "Doktoro" meaning "Doctor" in the new language and "Esperanto" meaning "he who hopes". As the booklet moved around the world, letters began pouring in, many written in what people were calling "Dr Esperanto's International Language" - a name soon abbreviated to "Esperanto".

After 12 months, Zamenhof published the names and addresses of 1,000 supporters, among them the secretary of the American Philosophical Society. In Germany, members of the World Language Club printed a magazine in Esperanto, and by 1905, it was time to pull everything together and call the first Universala Kongreso, or Universal Congress. Nearly 700 Esperantists from 20 countries assembled in Boulogne to converse in the new tongue and, quite soon, Schleyer's Volapük was history.

But as the advancing century grew ever more bloody, Zamenhof's hope that this new form of communication might elevate the human condition was to be sorely tried. Alongside his medical work, the doctor developed his ideas through correspondence with enthusiasts around the globe. But by 1917 he was exhausted. He died aged 57, while the worst human conflict the world had yet seen still raged around him. And worse was to come. Had he lived another 20 years, he would have seen Esperantists being rounded up and shot. Even Zamenhof's hopes might not have survived such a blow.

In the 253rd edition of Orienta Stelo, the newsletter of the Eastern Esperanto Federation, there's an item recording the sad passing of Phyllis Strapps. "Strappo", as she was known, was born in the Fenland city of Ely in 1905 - the very year of that first congress in Boulogne. In her early 20s, having moved to Ilford to work as a teacher, she discovered Esperanto, and for more than 70 years she remained loyal to Zamenhof's philosophy, teaching the language to anyone who would learn it, and travelling the world to meet fellow Esperantists.

Hers was a life of endless evening classes - of diplomas and socials and Esperanto weekends at her beach chalet in Felixstowe. In her front window at home was a sign saying "Esperanto parolata" - Esperanto spoken here - and in her spare room a bed was always made up for Esperanto guests. But if all this suggests little more than a harmless enthusiasm, then it is only half the story. For the years of Strappo's life spanned the hardest of times for the language she loved.

. . |

| Image by skanita in Wikimedia.Public Domain |

Within a few years of Zamenhof's first brochure, Tsarist Russia banned all publications in Esperanto. Groups of revolutionary Esperantists were springing up across Europe and the world's ruling elites were alarmed. Soon, Stalin would call Esperanto "that dangerous language" and Hitler would describe it as a tool of Jewish world domination. When Iran proposed that Esperanto be adopted by the League of Nations, France blocked the move and promptly banned the language from schools. Meanwhile, governments across central Europe actively discouraged Esperanto, no doubt fearing what would happen if workers of the world could share their experiences and aspirations.

By the 1930s, both Germany and the USSR had outlawed Esperanto organisations. The Nazis exterminated speakers they came across in their occupied territories, while Stalin, who spoke of "the language of spies", had Esperantists deported or shot (the Soviet government maintained controls until the late 1980s).

In Japan in the 1930s, Esperanto speakers were similarly persecuted, and even killed. They were notably described at that time as being "like watermelons - green on the outside but red inside" (green was adopted early on as the colour of Esperanto). In one of those twists of history that set the head spinning, rightwingers in the US were to use an identical jibe against environmentalists decades later.

The suspicion that Esperanto was a communist plot made it similarly unpopular in Franco's Spain, and many Esperantists had indeed fought on the Republican side during the civil war. But while China's nominally communist government has from time to time encouraged its use for official purposes, private use of Esperanto was ill-advised during the Cultural Revolution. And the persecution continues. Iran's mullahs dislike Esperanto, and Saddam Hussein had one teacher of the language deported. In recent years, two Swedish Esperanto speakers were severely beaten by Tanzanian police for attempting to teach the language.

Like any movement, Esperanto has also faced internal dissent, notably from an early breakaway group who devised an "improved" version called Ido. The Idists were frustrated at the refusal of the growing Esperanto movement to modify any of Zamenhof's basic rules. But while Zamenhof's "fundamentals" are indeed sacrosanct (Esperantists place great importance on structural stability), the Doktoro always insisted that Esperanto was not his property. Rather, he saw collective ownership and the creation of a language community as essential to survival and growth; a policy that, years later, was to receive vindication from the most unexpected quarter imaginable.

It was during the early 1960s, at the height of the cold war, that the US army, busily devising ever more realistic training scenarios, decided to create a fictitious nation to serve as an opponent during intelligence exercises. These "aggressor" forces (heaven forbid that the US would ever raise a finger other than in self-defence) were kitted out with green uniforms complete with insignia of a strangely Soviet appearance. And, as part of their fabricated identity, they were given a language.

And so it was that, in 1962, there appeared a field training manual bizarrely entitled Esperanto: The Aggressor Language. And while Esperantists are mortified that the language of peace and cooperation was ever tarred with the brush of aggression, and are quick to point out that the booklet contained several errors, they must also take comfort from the brief description that appeared in its introduction.

Zamenhof's "neutral interlanguage", said the manual, had been chosen because it was "not identifiable with any alliance or ideology" and was "far easier to learn and use than any national language". And in words that, while betraying a less than perfect grasp of English, would nevertheless have warmed the heart of the good Doktoro, it went on: "Esperanto is not an artificial or dead language. It is a living and current media [sic] of international oral and written communication. Its basic rules of grammar are such that it will remain a live language because it can assimilate new words that are constantly being developed in existing world languages."

Source: Newnham, D. (2003, July 11). A beginners guide to Esperanto. Retrieved March 12, 2016, from http://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2003/jul/12/weekend.davidnewnham

Pregunta Verdadero-Falso

Retroalimentación

Verdadero

Zamenhof knew that no existing language would fit the bill.

Retroalimentación

Falso

Esperanto is simple, regular, phonetic and orthographic.

Retroalimentación

Falso

He wasn't alone in treading this difficult path. Pascal, Descartes and Leibniz all toyed with constructed languages

Retroalimentación

Verdadero

Retroalimentación

Falso

He said that Esperanto was not his property. Rather, he saw collective ownership and the creation of a language community as essential to survival and growth.

Actividad desplegable

Match the words with their meanings.

Importante

"The popularity of Esperanto in several countries was proof of Zamenhof's pudding"

The proof of the pudding is in the eating is a proverb that means: you can only say something is a success after it has been tried out or used.

Considering the conflicts in the world today, is there any use for Esperanto? Do you think that an international global language such as Esperanto is feasible nowadays? Which countries would be in favor? Which countries would be against an international language?

Share your views with your partners.